Press

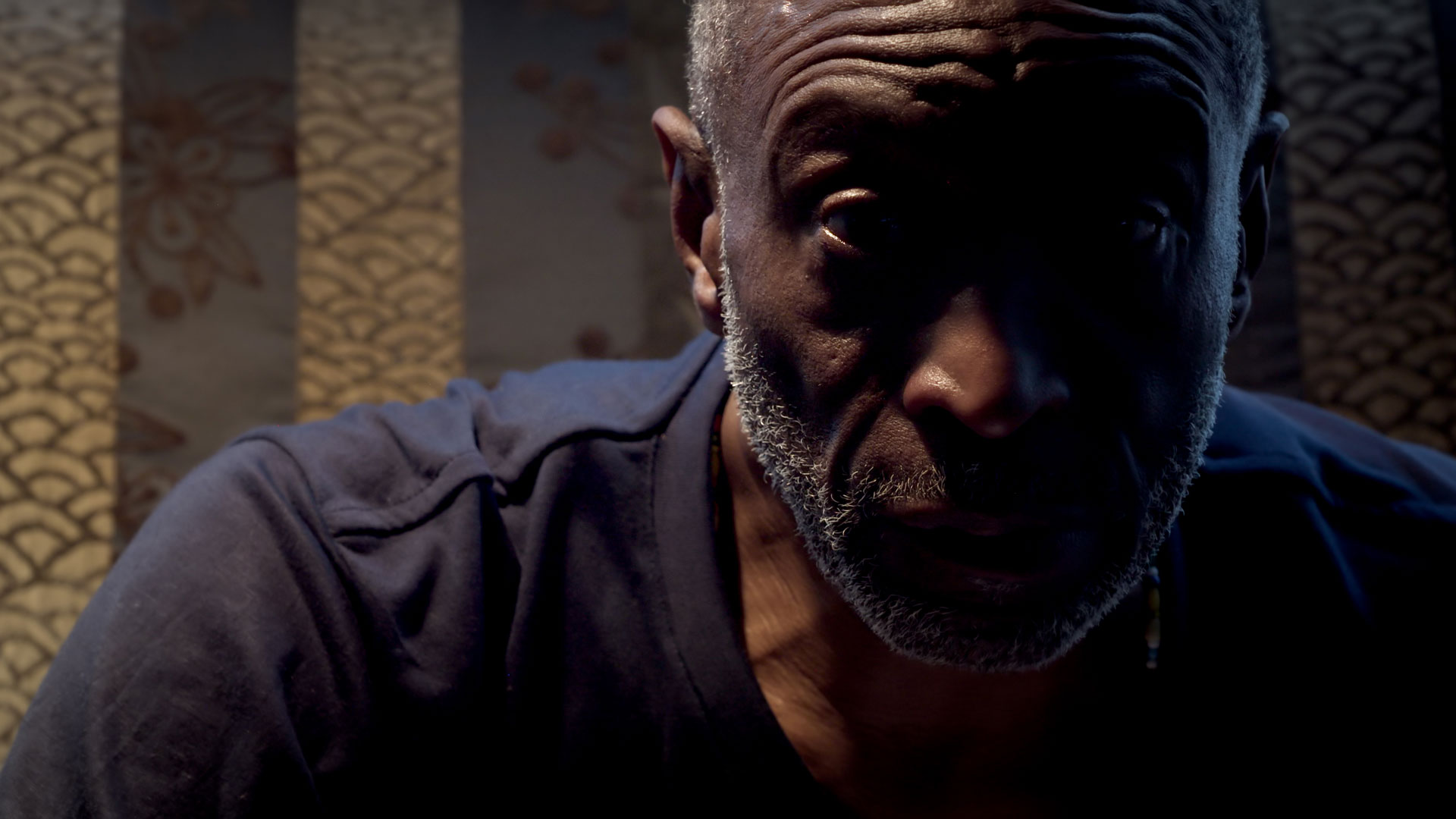

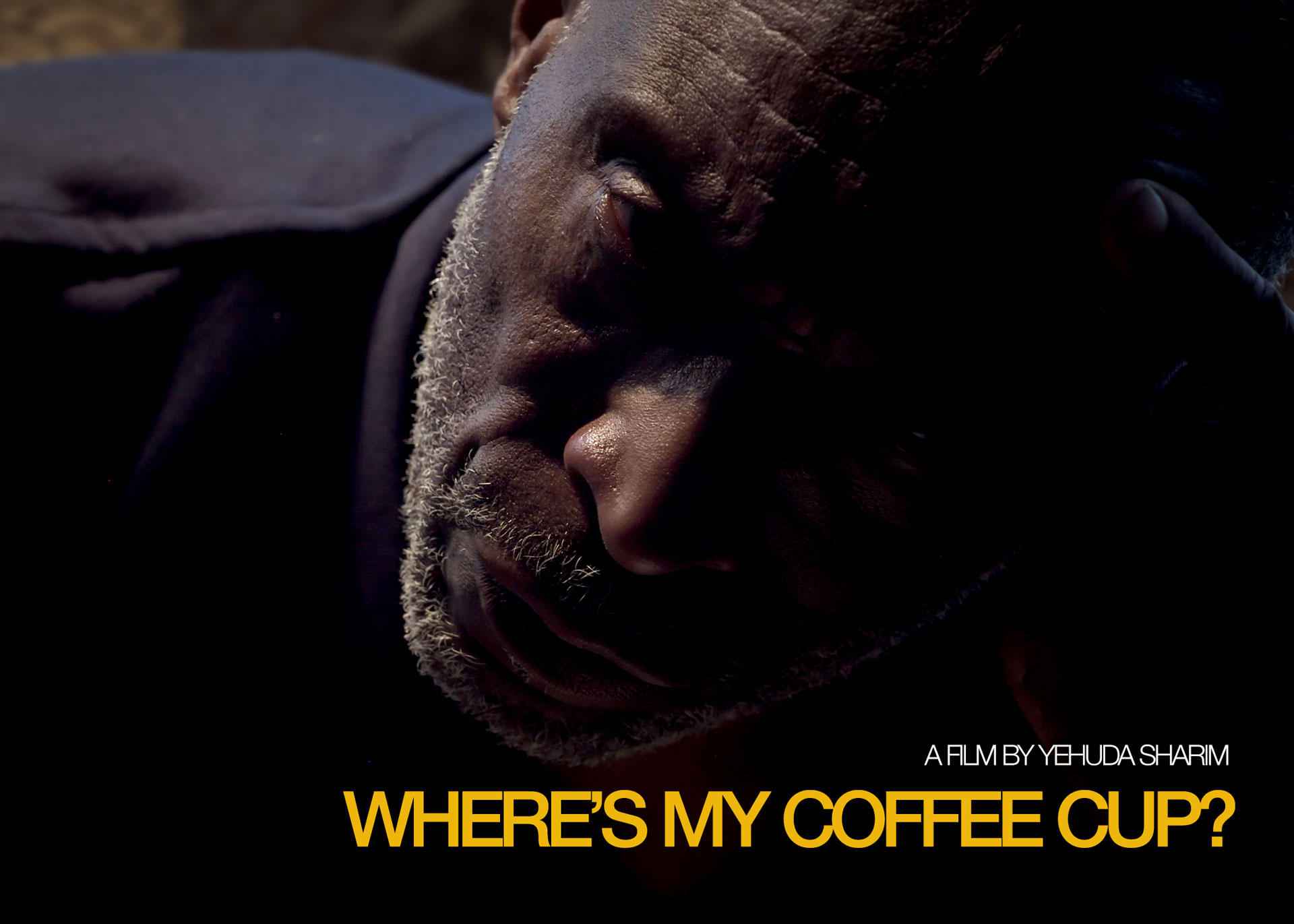

Where's My Coffee Cup? tells the story of John, who, at 64 and still in prison, must navigate trauma and aging in a space that is not designed for a geriatric population. Like others, he faces the challenges of stairs, top bunks, food that is not made for human consumption, and the everyday risks of violence and exploitation. John’s story is a call and demand for compassion and justice.

Reviews

The number of human beings 55 or older in this country's prisons is five times greater than three decades ago, and evidence of mistreatment and violence directed at this aging population is also on the rise. If you don't believe it, read the reports and, more importantly, watch Yehuda Sharim's film Where's My Coffee Cup, a visual lament in which the voices of aging imprisoned human beings and their loved ones decry the physical and psychic violence, injury, harm, and loss they endure while existing in prisons turned waiting-to-die warehouses that produce and facilitate far more than prescribed punishment and supervision. The voices in Sharim's film sing despair and demand public "response-ability."

Virginia's largest public employer - its prison agency, self-billed as a "premier correctional organization"- professes to provide "care and supervision," but the pleading voices of incarcerated human beings in Yehuda Sharim's film Where's My Coffee Cup tell another story, one decrying the absence of care, and the accumulation of physical and psychic harm, injury, and loss for aging human beings wasting away in what are effectively waiting-to-die warehouses. This film listens to and amplifies the cries of those captive poetic and disheartened voices - "If more people knew what goes on in here, they may care more" - over images of Virginia's historically fraught and haunting fields and waterways. Questions about aging, illness, crime, punishment, sentencing, love, race, family, society, and death form the score for this film, if only we would listen.

Yehuda Sharim dazzles yet again with his ability to bring humanity and compassion to the world‘s darkest places. Where’s My Coffee Cup compels us to look directly into the faces of mass incarceration and grapple with its enduring consequences.

This short film - which is both difficult to watch and hard to turn away from - puts a face on the lasting consequences of policy decisions made in the late 20th century. In the 1990s, the United States embarked on an experiment of addressing crime through mass incarceration. This led to a tremendous surge in life sentences, and today, there are five times as many people over the age of 55 in prison as there were in 1991. Sharim’s film shines a light on the large and small indignities faced by an aging prison population, and consequently, helps us to reckon with an often-hidden aspect of our criminal legal system.

This film is mesmerizing.

I think I've heard that said about a movie before, but I've never seen anything that actually was until right this moment.

The words and images pull you through the screen into the lives of people who have spent decades in prison and are now living the nightmare of geriatric incarceration.

Most people have not had the privilege of having their hearts broken when dear friends, colleagues, family, and mentors have died quickly from liver cancer that was diagnosed too late within carceral facilities, or seen strong men, role models, confined to prison wheelchairs because of MS. They haven't seen the kindest of people come out of prison after forty-nine years and try their best before eventually overdosing on fentanyl. They don't know the triumph of people who have suffered incredible injustices, achieved commutation, and worked every day from their late sixties until their mid-seventies to build a life for themselves by helping others. Most people need to see this film. Everybody should see this film.

Pierre Schouver, C.S.Sp. Endowed Chair in Mission

Elsinore Bennu Think Tank for Restorative Justice, Founding Member

“Where’s My Coffee Cup” is unlike any testimonial, documentary, or investigative project I have ever encountered. Refusing narratives of transcendence while dwelling in the protracted longing of an elder held captive by the state of war crystallized in the prison industrial complex, this film enacts an unsettling poetic intimacy with carceral genocide.

There is no convenient solution to this condition, only a permanent reflection on the fraudulence of the reformist dream. There is no fixing this terror, nor is there a method to render it more humane. This is a time-and-flesh distorting violence against body, memory, time, and the capacity to love-and-be-loved. John:

“I don’t know how I’m going to get out of here;

I just know I can’t do this shit another year...”

“Where’s My Coffee Cup” moves in ways that escape easy narrative grasp. It will take a while to absorb this gift. In the lingering, be grateful to John for exemplifying a creative, artistic, militant refusal to fade away.

Prison blurs perspective with each passing year. No one ever knew before how much a coffee cup can matter or why, and as crazy as it sounds on the surface, anyone bringing an open heart to the audience will never again doubt that John was entirely righteous in his outrage over its confiscation.

Having spent a decade inside around friends who have spent many more, I have never seen or conceived it possible for a film to so deftly and elegantly display the tension of aging in prison like "Where's My Coffee Cup?". Minutiae and dignity intersect tensely in John's accounting of how something so small can be so big in a place so heavy.

Accoutrements of normalcy and symbols of solidity and sanity develop outsize importance amidst the chaos and insanity of the system, surrounded by the suffering of lost hope.

Yehuda Sharim's masterful piece captures the absurdity, pettiness, and injustice of the "justice" system in the former capital of the confederacy. Even more impressively, it captures the non sequitur angst catalyzed and internalized in John and everyone else who has spent years wondering what more they can possibly take away for no apparent reason but cruelty.

Reviews

The number of human beings 55 or older in this country's prisons is five times greater than three decades ago, and evidence of mistreatment and violence directed at this aging population is also on the rise. If you don't believe it, read the reports and, more importantly, watch Yehuda Sharim's film Where's My Coffee Cup, a visual lament in which the voices of aging imprisoned human beings and their loved ones decry the physical and psychic violence, injury, harm, and loss they endure while existing in prisons turned waiting-to-die warehouses that produce and facilitate far more than prescribed punishment and supervision. The voices in Sharim's film sing despair and demand public "response-ability."

Virginia's largest public employer—its prison agency, self-billed as a "premier correctional organization" —professes to provide "care and supervision," but the pleading voices of incarcerated human beings in Yehuda Sharim's film Where's My Coffee Cup tell another story, one decrying the absence of care, and the accumulation of physical and psychic harm, injury, and loss for aging human beings wasting away in what are effectively waiting-to-die warehouses. This film listens to and amplifies the cries of those captive poetic and disheartened voices—"If more people knew what goes on in here, they may care more"—over images of Virginia's historically fraught and haunting fields and waterways. Questions about aging, illness, crime, punishment, sentencing, love, race, family, society, and death form the score for this film, if only we would listen.

Written by Nigel Hatton

03/28/2025

Key Cast

Arthur Burton as "John"

Michael Pittman

Olivia Rosinski

David Smith

Norma J. Smith

Shakil Ali

Featuring

Director

Producer

Original Music

Writer

Sound Mix

Sound

Tech Specs

Genre

Runtime

Completion Date

Country of Origin

Location of Filming

Language

Shooting format

Film Color

Image Gallery

Explore visuals from our film's journey.

.jpg)